Boundary lines make up much of the Richard Taittinger Gallery’s current exhibit, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? — lines that, like borders, criss and cross, divide and obscure. The show’s title is meant to signify contemporary African art taking its seat at the table of the “mainstream” art world — a proposition that feels, at best, fraught when you consider the white, Western traditions governing that table and much of Africa’s modern, colonial history. Consisting of the work of 12 artists, this well-curated show touches on these tensions and composes a vision of an emerging identity, a face taking shape. Advertised as an exhibit that “celebrates the growing impact of African art on the global stage,” it is about cultural presence, identity formation, and visibility.

Boundary lines make up much of the Richard Taittinger Gallery’s current exhibit, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? — lines that, like borders, criss and cross, divide and obscure. The show’s title is meant to signify contemporary African art taking its seat at the table of the “mainstream” art world — a proposition that feels, at best, fraught when you consider the white, Western traditions governing that table and much of Africa’s modern, colonial history. Consisting of the work of 12 artists, this well-curated show touches on these tensions and composes a vision of an emerging identity, a face taking shape. Advertised as an exhibit that “celebrates the growing impact of African art on the global stage,” it is about cultural presence, identity formation, and visibility.

Chike Obeagu’s “Isu Ewu Na Nkombi” (2015) features figures with bulging eyes and lips, paper cutouts from advertisements in what are probably European magazines. These characters, whose skin is similarly collaged in racially ambiguous tones, are sprawled at café tables, sipping drinks by the crown-jewel brands of a white, Western colonial and capitalistic empire: Coca-Cola, Moët & Chandon, etc. The subjects’ expressions are somewhat listless and heavy with their patchwork, plastic-surgery-enhanced features. The only figure that isn’t an indistinguishable nude shade is the shadowy waiter/butler. In a sense, Obeagu’s scenes — another shows its subjects in a gallery, another on a date — are completely ordinary, but they manage to produce a feeling of anxiety and suggest, in their nervous recombination of features, that like the paintings’ precarious balance or that of the capitalistic society theydepict, things are only just hanging together.

In Halida Boughriet’s photographs, rooms are divided by broad-striped walls in combinations that look like they could be national flags. The subjects are all highly posed, the rooms decorated with objects and furniture that recall a colonial library or otherwise anachronistic quarters. Gender and race are the other clear differentiating forces in these images, the black, white, and brown, male and female subjects positioned to offset one another against the backdrops’ hard divisions.

In one, “Les enfants de la Republique” (2015), a young black boy is staged in an armchair-cum-throne and positioned between two bookshelves. One side holds leather-bound copies of encyclopedias and indexes — presumably representative of the canon — while on the other, books without any identifying characteristics are blurred into the background. Between them exists a void, a black gap, suggesting a before and after. Time becomes as important to the story as distance and space, and in this case, the past is left undefined and in some ways negated, like the female subject in shadow underfoot.

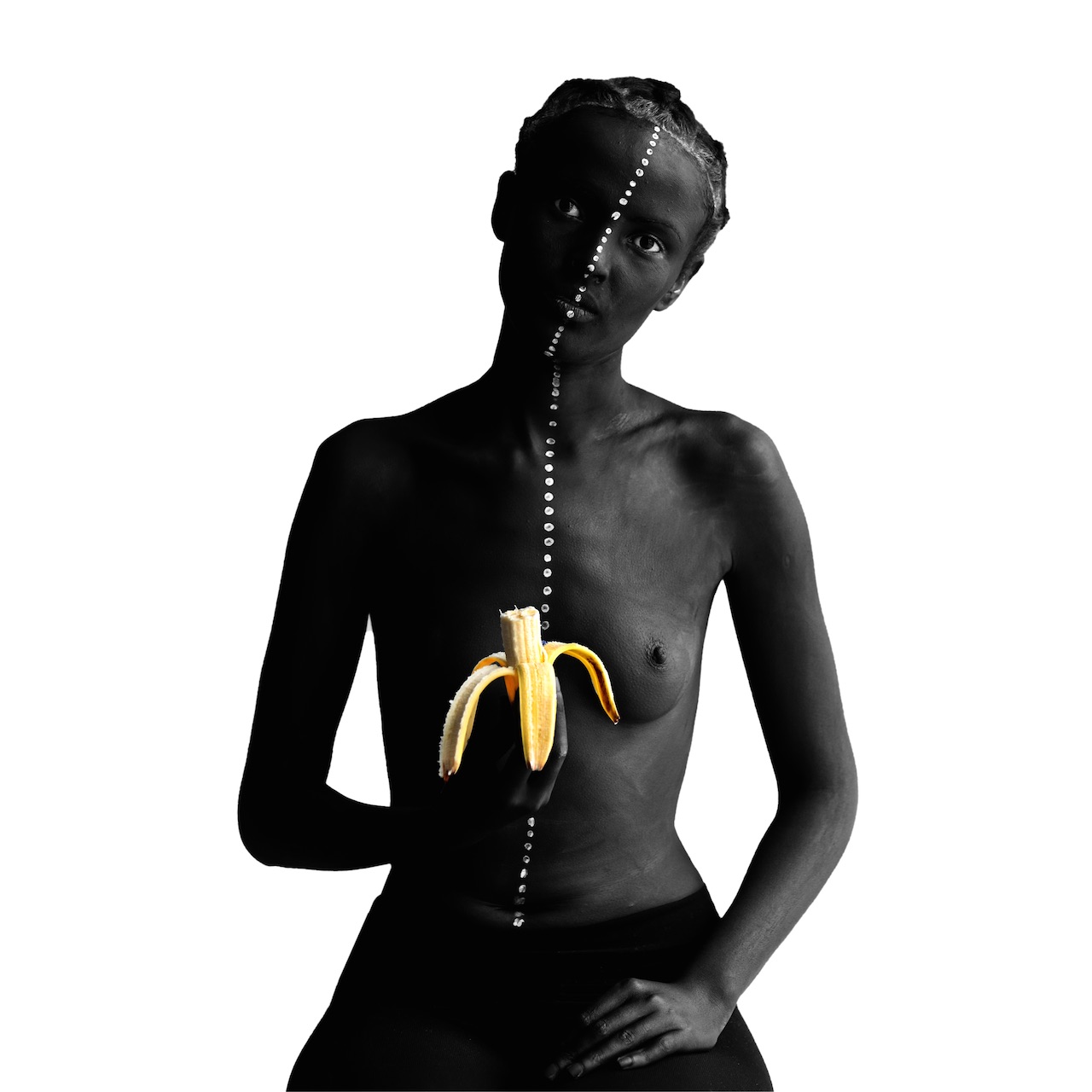

Similarly, Aida Muluneh’s three-paneled portrait (“The Wolf You Feed,” 2014) of a black woman at different stages of peeling and consuming a banana clearly announces that, whatever we make of the past, there’s no going back. At her center, the woman is bisected by yet another dividing line. There’s something tribal in her nakedness and the decorative effect of the chalk-white, dotted line that bisects her face and torso. She is of two aspects: one half of her body is black without definition, like a shadow; the other half, also black, is radiant, the light glancing the contour of her clavicle and breast and bringing her nakedness into consciousness. In the final panel, having taken a bite of the banana, her head is tilted in an inquisitive expression. Like Eve, the original woman, after eating the apple, there is no going back.

Alongside Muluneh, Onyeka Ibe, Beatrice Wanjiku, Ephrem Solomon, and Malia Ramanakirakina all use portraiture to convey the process of identity formation. Notably, in Ibe’s aptly titled “Identity” (2014), an indistinct face wades toward the viewer through a sea of red, choppy brushstrokes. They intersect in thick lines and at hard angles. The red, like blood, picks up on violent splashes of the same color in several other pieces in the show.

Onyeka Ibe’s “Identity (Self Portrait 1)” (2014) at far right (click to enlarge)

In the essay “Concerning Violence” from The Wretched of the Earth, the postcolonial philosopher Frantz Fanon poses the question: can oppressed people, subjugated by the threat and acts of violence that enforced colonization, only achieve true liberation by meeting violence with violence? And indeed, Guess Who’s Coming references the countless examples of violent struggle for liberation that make up so much of the history of Africa’s independent nations and became central to the process of decolonization.

French-speaking former colonies are a part of this history, and one of them is presumably the country of origin of Amalia Ramanankirahina’s haunting photo series Portraits de Famille (2014). These works deface old black-and-white photos of well-dressed ladies of the early 20th century and decorated military men. But who are they? Their faces are obscured by strange net-like smears. Are these Africans? Are they even black? Are they colonizers? What is our relationship to this history? As in Muluneh’s and Boughriet’s works, we are left to ponder the past and its meaning, without any of the details.

These questions and historical threads converge like traumatic memories in Guess Who’s Coming and ultimately deposit the artist at the center of this process of decolonization and national identity formation. Perhaps most compelling is the sense that you’ve caught these artists in the middle of a project that, like the process of liberation for Black Americans (experiences that are difficult to disentangle when the show’s title nods to the American film of the same name) remains a work in progress.

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?continues at Richard Taittinger Gallery (154 Ludlow Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through August 22.